Guest post by Avery Farmer ’20

When I visited the British Royal Observatory in Greenwich during a vacation in London this year, I was captivated by a series of rooms dedicated to a history of time. Not time, the grand spiritual and scientific setting of our own existence, but humans’ attempts in the last 500 years to measure that constant force. On display were indecipherable jumbles of pendulums, springs, and gears, exposed or half-concealed by elegant metal dials, each new model claiming some slight advantage over the last. The placards described innovations like a redesigned spring that made an early chronograph a half-second per hour more precise than its predecessor, or the first design that compressed the great workings of a five-foot-tall clock into a pocket watch. My fascination with these old instruments, clumsier and less accurate than the almost-perfect time immediately available on my iPhone, seems silly for a citizen of the digital age. If I cared about cutting-edge science and the thrill of innovation, why was I looking at centuries-old clocks instead of looking around an Apple store? Though they were once great leaps forward, the instruments that I beheld in Greenwich were no longer revolutionary; they had become redundant. So where did my fascination with them come from, and what did it mean?

I think the intense relevance that those old clocks took on speaks to a broader appeal of historical archives in the digital age: their physicality engages us as participants in ways that digital media doesn’t, and that gives us a rare feeling of connection. I’ve worked for a year now in the Digital Programs department of Amherst College’s archives creating digital images of objects from the archives. Over the past year, I’ve taken pictures of photographic negatives of college life in the 1970s, a student’s letters home from the mid-1800s, a first printing of an early collection of Emily Dickinson’s poems, a woman’s diary in Europe during World War II, and the poet Richard Wilbur’s handwritten revisions. Unlike the authors of all of the objects I’ve digitized, I’m a millennial, a citizen of the digital age. I was born in 1998. I grew up with a computer in the house, surfing the internet. My mom letting me have a Facebook was the most exciting part of becoming a teenager. All of the music I know today, I heard first on an iPod. When I took this job, I didn’t expect that it would cause me to reflect much, but a year’s engagement with physical records of people’s lives has given me a lot to think about, both the meaning of digitizing archives and what archives can teach me.

I remember being struck by the Katrin Janecke Gibney diaries, which are a series of diaries kept in secret by Gibney in Berlin during World War II while working for the Nazi propaganda ministry. I only learned that she was working for the Nazis after reading the diary for some time. I had assumed she was against them, and her involvement in the Holocaust deeply troubled me, as it ought to have. Her handwritten record of her life captures the way that her daily life was impacted, but not always dominated, by the ongoing war. Interestingly, it also references frustrations with the limitations sexism placed on her. For example, on Saturday, May 16, 1942, she writes, “No, I am not made up like other women. For instance I cannot talk about dresses and food, while men discuss about the existence of God and similar problems, as they did tonight at Homer’s party.”

However, a few years later, war begins to dominate the diary. On April 25, 1944, she writes, “A boy that I used to know has been beheaded [for defeatist remarks,] those of the kind that we all make daily, against the war and against the regime. Everybody of us is ‘guilty’ in this sense and ripe to be killed.” She remembered him creating satirical cartoons against the Allies.

These objects are complicated. The phrase that comes to mind is Hannah Arendt’s notion of the banality of evil. In the entries that I read, Gibney comes across as—for lack of a better word—ordinary. She does not espouse unusually monstrous views in these pages; nor does she show a casual disregard for life. She has all of the concerns and considerations that most people of the time did: social life, politics, parties, et cetera. But at the same time, the reader has to make sense of Gibney in her own words in the context of her work in support of the Nazi regime. It’s an uncomfortable experience and requires an empathy that might be better spent elsewhere, particularly in the contemporary political moment where fascists and right-wing extremists are empowered.

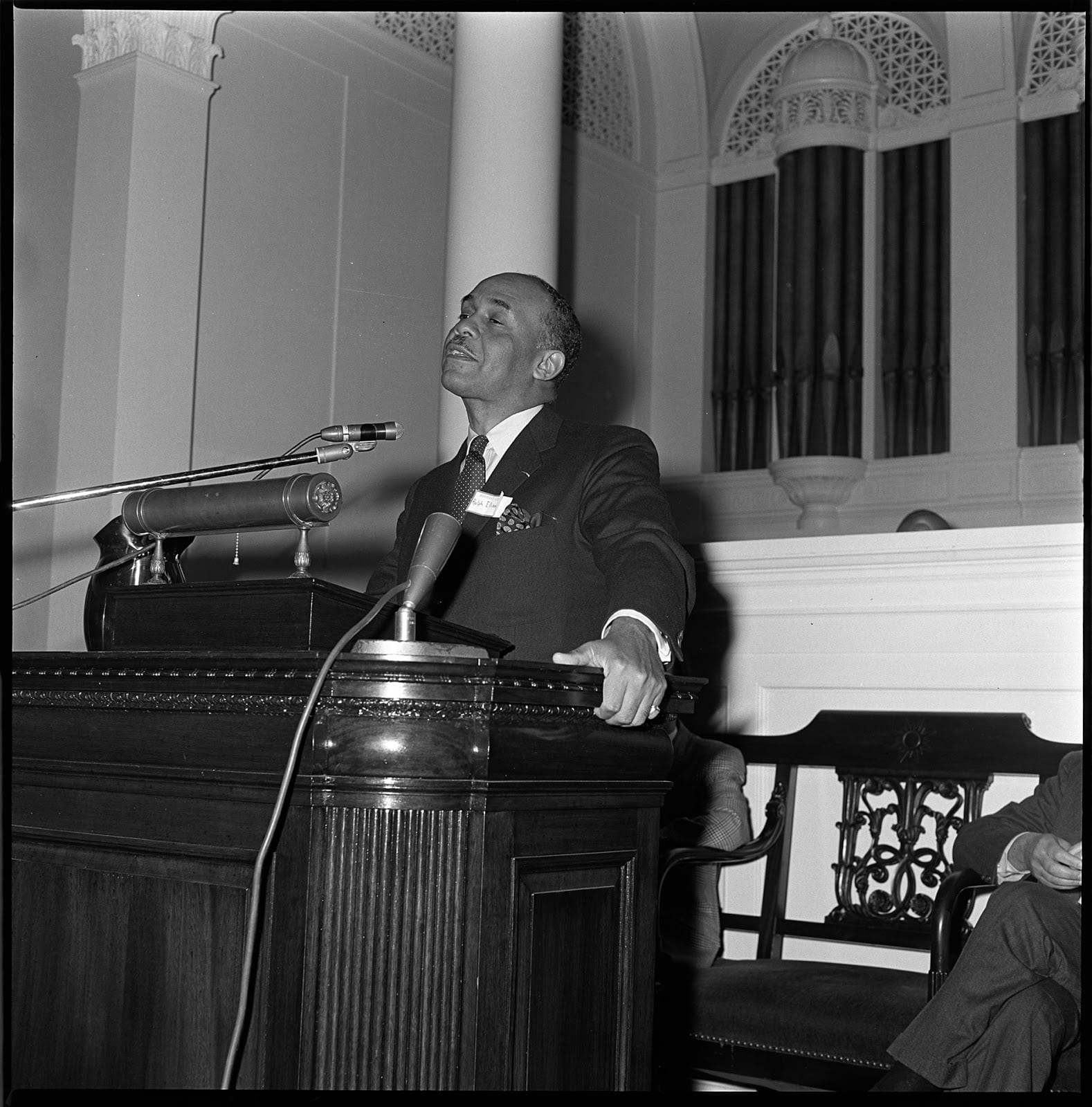

The college photographer negatives that I have worked on for the past few months are far more fun and mostly pleasant to work with. I’ve digitized over 4000 images from the mid-to-late 1960s. Some show fraternities engaged in the rowdy, sometimes offensive behavior that we now associate with frats, but others depict students and professors in walkouts and protests–of what is not always clear. In 1969, there was a three-day moratorium in which students and faculty walked out of classes to hold discussions and seek resolutions on race relations on campus. The activism of black students on campuses in the late 60s produced significant outcomes across the country, with scholar Martha Biondi asserting that the Black Power-influenced black students’ movements on campus were of even greater historical significance than the white-run antiwar protests of the time. It is a privilege to be able to witness this process at Amherst through those negatives. I also enjoy seeing images of notable people speaking at Amherst. My favorite images have been those of the acclaimed poet Sonia Sanchez, who was the second chair of the Black Studies department here and gave a reading of Gwendolyn Brooks in 1974; the pioneer of rock music Chuck Berry, who performed at prom in 1967, and the titan of American literature Ralph Ellison, who spoke during the 1969 college moratorium on race relations.

The most interesting effect that working on digitizing the archives has had on me is that I have begun handwritten correspondences with my grandmother, my best friend, and occasionally my mom. While at work I took analog communications and made them digitally accessible, at home I was taking communications which would ordinarily be digital and made them analog. I’m not sure which collection that I worked on here inspired me to do this, but I am drawn to the appeal of a physical record of my relationships with people. Particularly with the thoughtless ease of writing a text or email, the care and intention necessary to write something by hand deepens the emotion and expression of whatever you write. Partly because of that deeper connection, writing and receiving letters has had a significant effect on my time at Amherst, because those letters have calmed me and helped me to express myself.

Ultimately, after a year working in digital programs and thinking about archives, I’m reflecting on the relationship between digital and analog. What does it mean to create a digital source versus an analog one? What is lost, and what is gained, in choosing one or the other? I’m reminded of the imagined division between “civilization” and “wilderness”. Wilderness (analog) takes on a sense of old spirituality, and we associate time spent in nature/history with gaining perspective and wisdom. Civilization (digital), on the other hand, is often considered as the product of the best and worst of humanity: in civilization/the internet, everything is convenient but stressful, innovative but exploitative. I would like to end this entry with a quote from William Cronon about wilderness that I believe speaks to the complicated meanings of digital versus physical archives: “For many Americans wilderness [or a historical object] stands as the last remaining place where civilization [the digital age], that all too human disease, has not fully infected the earth. . . But is it? The more one knows of its peculiar history, the more one realizes that wilderness is not quite what it seems. Far from being the one place on earth that stands apart from humanity, it is quite profoundly a human creation.”

Avery Farmer will be a junior at Amherst College this fall. He’s originally from Ann Arbor, Michigan, and is majoring in English and Black Studies. He has worked for the Digital Programs Department since Spring 2017.