Guest post by Zehra Madhavan ’20

When I started working at Digital Collections as a Student Assistant during the spring semester of my freshman year, my understanding of Amherst College’s history was limited to facts I had read about in pamphlets and bits and pieces of information I had picked up in various lectures and speeches; little did I know that I would soon be encountering countless documents and archival items that would shape not only the way I see the college but also the way I see my place in this community.

The project I have been working on is the digitization of past Student Publications as part of the bicentennial goal. Through digitizing student magazines on topics ranging from literary works to events and issues at the school, I have been able to see firsthand how the interests and habits of Amherst College students has shifted as the school’s population has changed. For example, the works published throughout wartime were strikingly humbling as I read articles about students drafted into war, opinion pieces about America’s role on the world stage, and advertisements referencing day-to-day wartime life—circumstances that seem far removed from our current way of life at Amherst but nonetheless make up a significant part of our history. Those times may be difficult to imagine, but reading the school’s history from the voices of its past students made it more accessible and more grounded in the reality with which we are now familiar.

It was also fascinating to see the change from publications written by and for male students to those created by staffs comprised of men and women when the college became coeducational in 1975. I remember digitizing a document where a female student had written edits on a male student’s writing submission to one of the college’s magazines; she called attention to his potentially sexist tone and urged him to consider how the women on campus might perceive his piece. Gradually, the topics discussed in these publications became more diverse and catered to an audience dealing with new issues like political activism and on-campus movements. Unique documents like these provide a perspective arguably more illuminating than that of a history book or Wikipedia page.

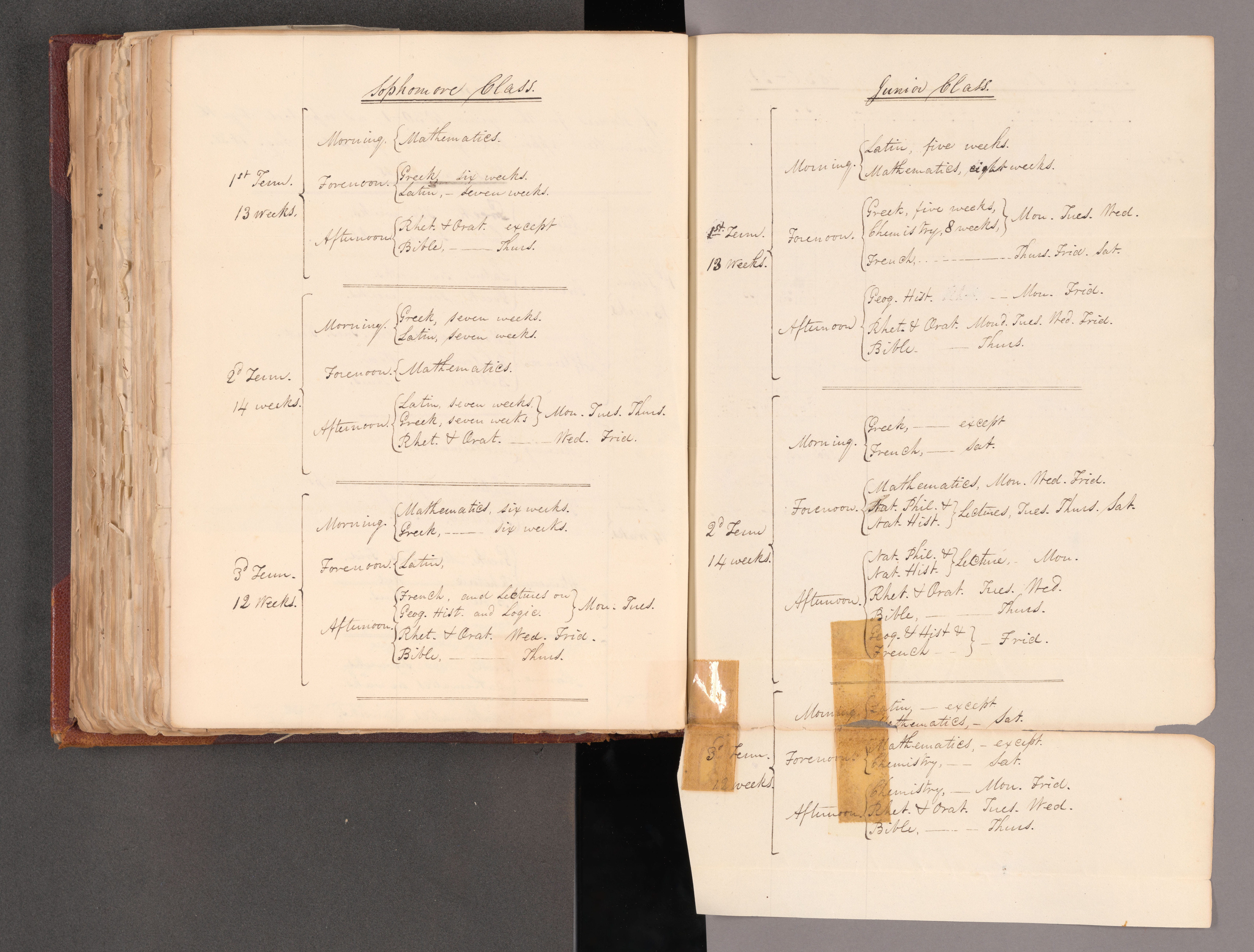

Another memorable project was the Dean of Faculty Minutes, which included a variety of interesting accounts of faculty discussion, student infractions, course deliberations, and more. When I read the class schedules that each student had in 1830, I was amazed at how much the course curriculum here at Amherst has changed since the college’s early history. The freshman class schedule was limited to Greek, Latin, Mathematics, Rhetoric, and Bible, and the only change between semesters was the order of these set classes. As a sophomore, students were introduced to French and “Lectures on Geographical History and Logic,” then eventually upperclassmen would take chemistry, natural history, and philosophy courses; however, just over a century later in 1939, the course offerings had already expanded far beyond those subjects. Amherst offered electives in a variety of fields like anthropology, astronomy, drama, economics, geology, art and more subjects familiar to us today.

This search prompted me to research how exactly Amherst came to adopt the Open Curriculum, which is one of the main reasons I chose to attend Amherst and a system that all Amherst students benefit from today. I learned that in 1967, Amherst announced in the Course Offerings publication that they chose to abandon the Core Curriculum in favor of a more open curriculum with three required interdisciplinary “Problems of Inquiry” courses intended to round out students’ liberal arts education. By 1972, the college got rid of Problems of Inquiry courses and instead just required students to complete a certain number of courses, regardless of department, in addition to a chosen completed major.

Now, instead of strict offerings, we are encouraged to explore paths that we may not have considered in fields so much more varied and unique. When I compare my schedule—with its Asian literature, film studies classes, foreign language classes, and more—to those delineated in the early faculty minutes, I can’t help but feel immensely grateful for and impressed by the generations of faculty who have shifted the needle, creating the opportunity for students from all over the world to congregate and study whatever makes them passionate.

Of course, my own identity as an Asian-American woman has shaped the way I interact with the works I digitize, too. It’s impossible to ignore the fact that the bulk of archival material from the college’s early days was written by, about, and for white men. Through digitizing the Amherst Alumni News documents, I’ve encountered biographies and articles about the many influential figures for whom majority of the buildings on our campus are named. While these documents have taught me a lot of interesting facts (Did you know Gilbert Hovey Grosvenor, class of 1897, was the first editor of National Geographic?), they have also reminded me that we are still in the process of remaking the college’s identity, gradually gearing it toward greater inclusivity and diversity not just in terms of course offerings but also in terms of community and student identity. Delving into the college’s history through documents can help broaden our understanding and inspire this process even further, and to me, this makes the digitization job even more significant and important.

Zehra Madhavan ’20 is a junior at Amherst College. She is originally from Princeton, New Jersey and is majoring in Math and Asian Languages & Civilizations. She has worked for the Digital Programs Department since Spring 2016.