I worked on the digital projects of the colleges archives for all but my first year as a student at Amherst College, and over time the photographs, publications, and physical objects from the last two centuries that I encountered contributed to the way I thought about the college’s history and my own role in it. The archives were on my mind particularly often throughout my senior year as I tried to make sense of my time at Amherst, my upcoming graduation, and the adult life I would be expected to live after it. I thought of the archives not just as a site to research the past but as a foundational part of the college’s present, and they influenced me daily: from my time spent digitizing the negatives of the college photographers, I was excited to walk in the ritual procession up Memorial Hill on Commencement, still led today by the Hampshire County sheriff. After a special topics course that used the papers of Richard Wilbur (which have not yet been digitized but include notebooks from his own time at Amherst), I took pride in the work that I was completing for my classes, knowing that many great alumni once studied with diligence and curiosity the same texts that I was reading and writing about. Because of my years spent photographing the Student Publications collection and Amherst Student issues from 1959 to 1977, I was able to see my time as only part of the larger narrative of the college’s history. All of these perspectives came to me on accident, simply by the good luck of having a campus job that exposed me to the college’s history and enabled me to spend time considering its various artifacts.

That history was always on my mind, but in the days and months after receiving the news that most students would be ushered off campus by the end of spring break in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, I found myself thinking of specific objects from the archives in order to understand the disruption that we faced. Most prominent among these instructive historical moments were records of the college during World War II. In high school, right after I had committed to attending Amherst, my grandfather happened across a copy of the 1944 Olio at a yard sale. In the foreword, the editors reflect:

… we think [this edition] has not only a peculiar interest but a peculiar importance. Amherst is going through a period in its history that is unique and that will be looked back at with interest and curiosity. It was this fact that caused the College to come to the assistance of the 1944 Olio Board in deciding to assure the publication of this book, which should be viewed as primarily a record of Amherst in war, and somewhat less than usual as the yearbook of a class. We have tried to make this record as accurate as possible.

The copy that my grandfather collected seemed to have belonged to a student: some pages were bordered by handwritten military identification numbers and signatures. Even before setting foot on campus, I was intrigued by this record of the way the college responded when the nation went to war. In it, one finds evidence of a campus turned on its head. Military units march past Johnson Chapel. Photographs of the graduating seniors are accompanied by a note explaining, “The class was large when we began, but the armed forces have taken from the hill over two hundred men.” In individuals’ entries in the book, “U.S.N.R. V-7” appears next to athletic and academic achievements, indicating their participation in the voluntary naval officer training program begun by Franklin Delano Roosevelt to prepare the United States to enter World War II.

The juniors provide a more in-depth chronology of the changes that took place since their first year on campus:

In general, the record of our first semester was much like that of any entering class. We pledged fraternities, sang on Walker steps, drank beer at Barsie’s, learned the bus schedule to Hamp and South Hadley. We held bull sessions, yelled for ‘Obie,’ and struggled through History 1. Then came Pearl Harbor, and our life changed from a peace-time to a war-time schedule. The three-semester year was accompanied by harder work and the gradual shrinkage of the class as a result of the draft. But athletics, competitions, and parties continued. The majority of the class was here to thrill over the 12-6 victory, and it was not until President King asked the E.R.C. men not to register for the spring semester of 1943 that the first appreciable exodus came. Then the Army Air Corps was called in late February. This left but 82 Juniors on the campus. After college closed in June, sixty of these transferred to Williamstown and donned bell bottoms to study and train in the Naval Reserve. Of the remaining twenty-two the majority are pre-medical students; the others are not able to serve.

Apart from being fascinating first-hand accounts of the local effect of World War II, these sections of the Olio also provide compelling precedent for the Covid-19 pandemic’s disruptions at Amherst. Particularly the exodus of students from campus described in the Junior class entry made me feel at least some level of historical company as I conducted my own remote learning. Furthermore, the metaphor of a country at war has been used by many contemporary leaders to describe the efforts necessary to survive the pandemic, and witnessing the way that Amherst responded to an actual war helps to put our own sacrifices in perspective.

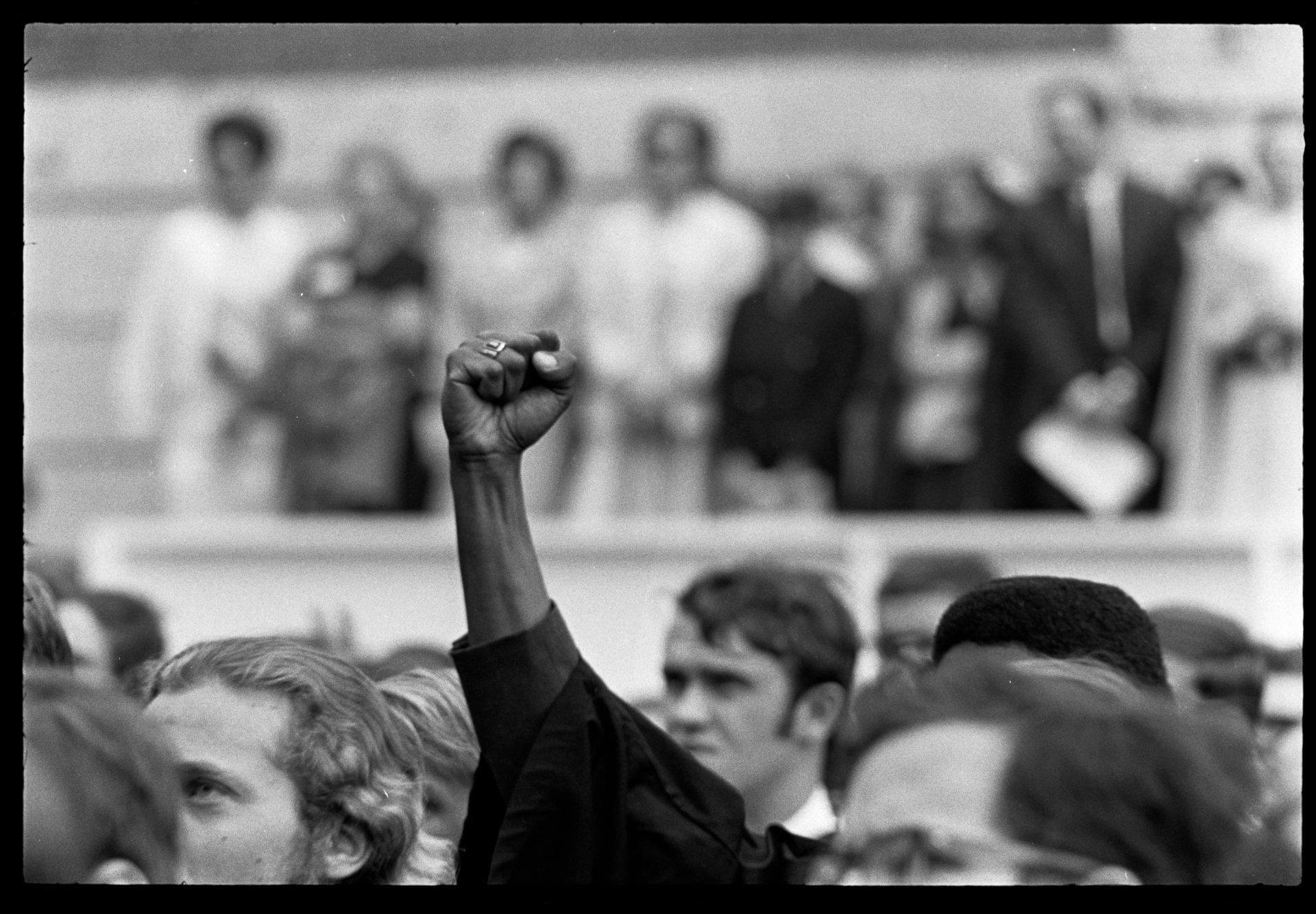

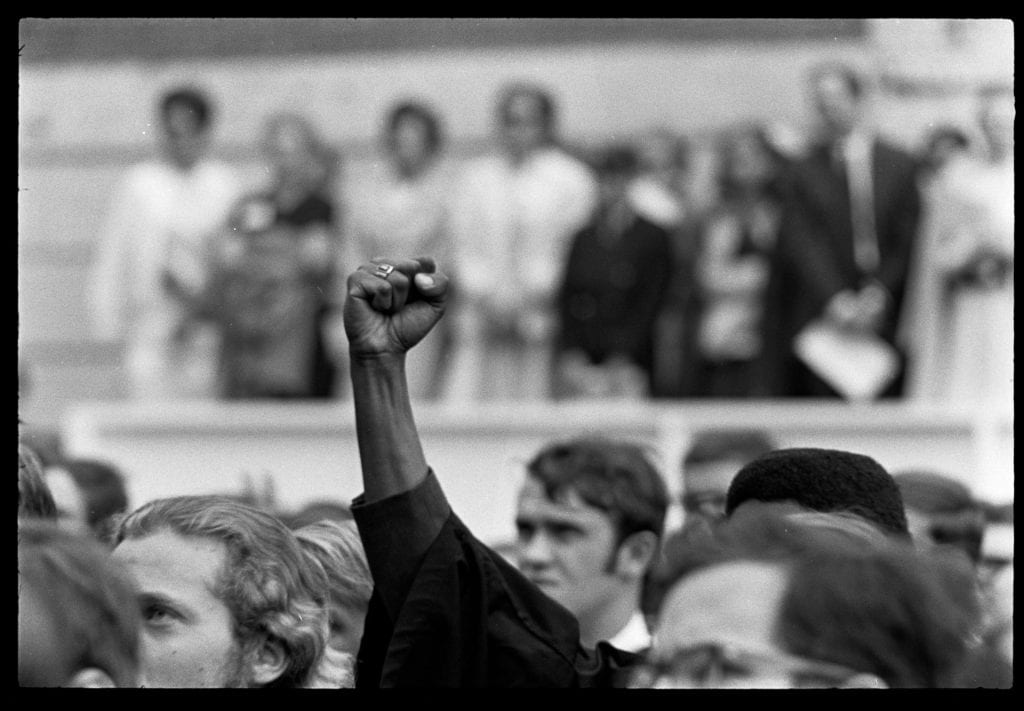

Like many people, I assumed that the Covid-19 pandemic would be the defining story of 2020, but as antiracist protests erupted across the country in recent weeks after the police killing of George Floyd, it became clear that we were living through two major moments at the same time. As I did with the disruption of the pandemic, I found present value and inspiration in the record of past movements for justice that were taken up on Amherst’s campus—of which there were many. Of thousands of images from the college photographer that I digitized, the one that endures in my mind is from the 148th commencement. In it, a black graduate raises the Black Power salute above a sea of white heads. The photograph calls to mind the 1968 Olympic protest on the 200m podium, which occurred one year previously. The graduate’s face is visible in the next photograph, but I prefer the composition of the first. This gesture at Commencement culminated a year of resistance at Amherst: there were two moratoria that year, the first in response to the Vietnam War and student uprisings on other campuses and the second in response to racist conflict on campus. It has been fifty years since then, and the example of students of that era inspires and compels me to take up a more active role in defining justice for the present moment

The last fifty years have seen Amherst students, faculty, and administrators act in pursuit of justice often: In December of 1978, the Latinx cultural and political organization La Causa occupied Fayerweather Hall to demand the creation of a space on campus to serve as a cultural center. Their protest resulted in the Jose Martí room, which still serves that purpose in the basement of Keefe Campus Center today. In 1972, President John William Ward was arrested with students at a sit-in against the Vietnam War. Countless other examples exist, but these have remained in my mind since I encountered them first in the digital projects lab—I would encourage readers to find other moments that speak to them.

In conclusion, then, after spending the better part of four years working on the digital projects of the archives, I am gratified by the surprisingly significant influence these collections have had on me. More than a dalliance in historical novelty or a way to pay the bills, my work in the archives became a fundamental part of the way that I view myself in relation to the college and the world. In my years after Amherst, I hope to recall the archives’ lessons in justice and historical perspective as I try to create my own impact on society, and I hope that the work I did will enable future years of students to enjoy the same deep exposure to the archives by way of the digital collections.

Avery Farmer Amherst Class of 2020. Originally from Ann Arbor, Michigan Avery majored in English and Black Studies. He has worked for the Digital Programs Department since Spring 2017.