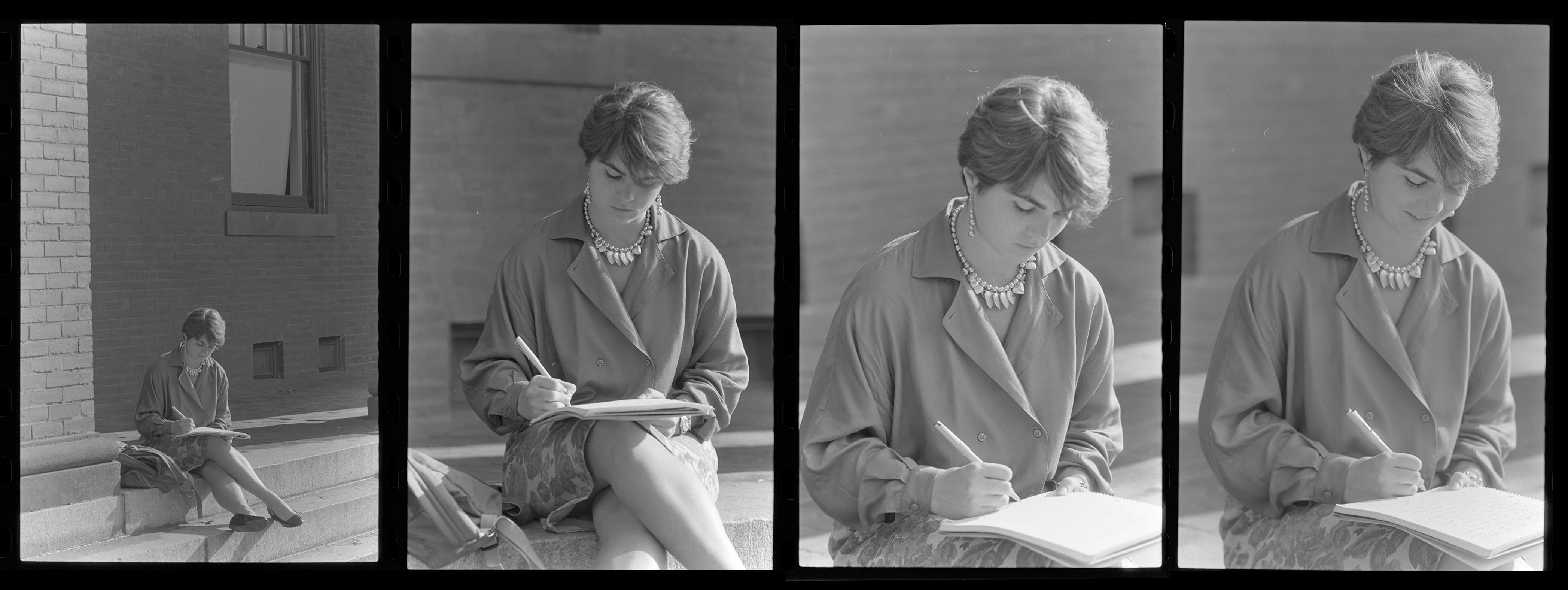

This month the Digital Programs Group began digitizing the College Photographers Records Collection. The collection includes more than 400,000 negatives taken by the official photographers of Amherst college from 1962-2005; A visual history of the college for the second half of the twentieth century.

Using negative collections housed in archives tends to be a challenge. Generally, negatives enter the archive housed in some sort of vessel—glass plates stacked in a cigar box, a disintegrating yellow envelope or an archival glassine sleeve. Each envelope may have a description and contain a couple frames of film or many rolls of film of various formats. The jumping off point for access may be date or description of the negatives. Once you think you might have found what you are looking for, a staff member needs to view the negatives on a light table in order to find something that might fit a specific purpose. Then comes the evaluation; is the image you want in focus, properly exposed, damaged by light leaks, scratched, or covered in dust? Before the advent of digital photography, a copy negative would be created to preserve the original and prints would be made in the darkroom. With the advent of digital photography scanners are now used instead of the darkroom.

A project of this scale is a massive undertaking, and rather then try to digitize the entire collection we are looking to digitize around 10%, or about 40 thousand images, in the next three years. Currently archive staff is prepping negatives for digitization by selecting, organizing, re-housing, and transcribing any pertinent information.

A project of this scale is a massive undertaking, and rather then try to digitize the entire collection we are looking to digitize around 10%, or about 40 thousand images, in the next three years. Currently archive staff is prepping negatives for digitization by selecting, organizing, re-housing, and transcribing any pertinent information.

Fortunately we were given the funds to purchase a new digital imaging system. Manufactured by Phase One this new camera captures about ten times the detail as a cell phone. Up until now, the library had utilized Epson flat bed scanners. While they do a fairly good job at scanning negatives, they are very slow; capture time can be a couple of minutes per image. The Phase One system will enable us to photograph a negative in a fraction of a second at a quality that surpasses the quality of a flatbed scanner. When photographing tens of thousands of images the time saved by switching to a camera system quickly adds up.

Over the years I’ve been fortunate to work on several mass digitization projects of negative collections; Leslie Jones Negative Collection at the Boston Public Library, MotorBinder ( a book focusing on the history of road racing in Northern California), and a collection of glass plate negatives of the 1919 international Panama Pacific Exhibition held at the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. Between these three projects I worked with many forms of photographs; 11×14 glass plate negatives, autochomes (one of the first color negative process), 100-year-old negatives that looked brand new, and 30-year-old negatives that looked like they had been peeled off the floor of a darkroom.

Each project brings its own technical and workflow challenges; different cameras and scanners, varying levels of student staff training, and developing unique workflows. All the work allows us to—in the end—look at thousands of images from a variety of sources. I find the real excitement comes from what photography does best. We’ll call it describing and suggesting. ‘This is a picture of that’ ’That happened here and this is an image of it happening’ Most of the things and people in these archives are long gone but the images are moments that have happened that I get to experience through my job. I now feel as though I have a visual connection to the 1919 Boston molasses flood , and what it was like to race cars in the San Francisco Bay Area in the early 1960’s.

I’ve been working as the Digitization Coordinator for a little less than a year now, and have limited context for the images we are digitizing. We are now in the third week of the project and still working through some technical challenges, but I’ve already seen some interesting images though my firsthand knowledge about their contents are limited. The labels provide a bit of context. Other times, they add to the puzzle.

Other examples of folder descriptions.

Sit-in Westover – Bill Ward

Day of Concern for Blacks

ABC House

What I find especially interesting are those digitized images without context;

Timothy Pinault is the Digitization Coordinator for the Frost Library at Amherst College. He can be contacted @ tpinault at amherst dot edu.