Innovation and disposability…

Technology innovation is a given in our fast-moving culture of social media and disposable devices, yet innovation isn’t all that drives the technology infrastructure underlying the systems we use everyday. In the library, we us many online resources driven by databases that organize, track, and deliver the content we need, when we need it. In some ways, a database is a lot like a library – books are on shelves, and we have a catalog that tells us where to find those books, and when someone comes looking for one we can help them find it.

At Amherst College, we are in the midst of a long process of improving our database system that manages our digital collections. And while innovation is a central factor in our migration planning, another theme is emerging around the notion of repair. If you think about it, repair is a necessary function of the world. We repair our heating systems when they stop working, sometimes it is a small fix, sometimes it requires a completely new system. We also repair less and less as our culture seems to move in the direction of disposability – it is often easier to replace things like toaster ovens than to repair them.

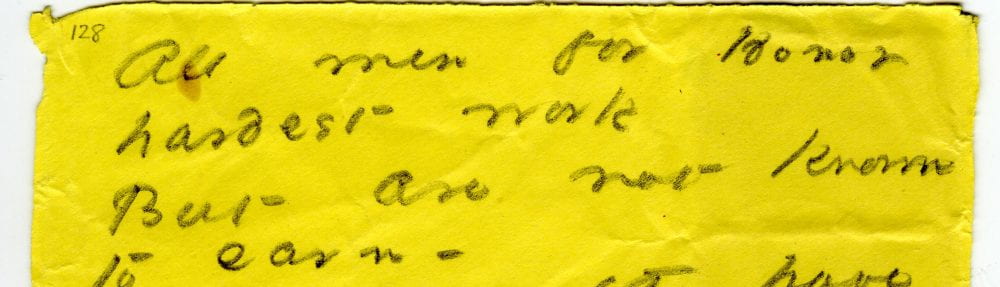

In the digital library world, we don’t have a lot of cheap, easily replaceable toasters. Most of what we are dealing with involves very fragile (yes!) digital objects that represent physical objects in our collections, like the envelopes that Emily Dickinson wrote poems on, or the first course catalogs in our college’s history. We can’t easily replace these digital objects and all the hours of work that goes into photographing and describing. We are reliant upon a stalwart digital system to keep things running smooth.

Digital preservation and digital repositories

We use the term digital preservation to point at what we hope to achieve, which is some kind of digital stasis of the objects we are storing and serving up online. Increasingly, the objects don’t have a physical surrogate, they are what we have labelled “born digital” and these are especially tenuous and fragile, to the point where we talk half-jokingly about printing things out just to have a backup physical copy. And it is our database systems, or digital repositories, that we entrust a good deal of our hopes for digital preservation. If we have a good system, we expect digital objects to persist over time without degradation.

At Amherst, we use the Fedora repository to manage our digital collections. Fedora is, in the landscape of digital repositories, kind of a like a star quarterback, at least in my mind. Everyone knows about it, knows it does what you will expect it to, and maybe also, everyone wonders when it will retire, because it is getting a little old. Fedora is a perfect example to me also of the idea of innovation mixed with repair. There are many things about Fedora that work well, and help us to steer in the direction of digital preservation.

But Fedora needs some updates, modernization, and reinvention. Fortunately, the community of Fedora users has been working over the past few years to conduct these innovations/modernizations and tweaks to the underlying infrastructure. One of the beauties of Fedora is that it is an open source repository, and is maintained by a community of users who have a stake and an interest in seeing it sustained and continuing to flourish. This is where repair meets innovation in my mind – because Fedora is also not like a quarterback. I like to think of Fedora as more like a barn – something that can continue to serve a purpose, and be repurposed, while also leveraging the type of thing it is and how identifiable it is in our culture.

Repair and innovation

I was exposed to this idea of repair as a corollary to innovation by way of Bethany Nowviskie, the director of the Digital Library federation, who wrote about the work of Steven Jackson, a information science researcher at Cornell, in her 2014 talk “Digital Humanities in the Anthropocene.” She relates his discussion of the notion of repair to resilience and to establishing communities of care, both of which concepts are critical if we are to engage in digital preservation and stewarding digital content for the long term. Steven Jackson brings many ideas to his chapter, “Rethinking Repair,” with a central idea of repair being way to prevent or prolong decay, while also being a mode of reinvention or innovation. Applying this notion to the work of the Fedora community, it is clear to me that Fedora is encapsulating ideas of repair in the work of the Fedora specification, and implementation of new features that interact more with the broader web while aiming towards sound digital preservation. Fedora is kind of ‘old’ in terms of a technology, having been around for twenty years, but it is still reinventing itself and evolving, and with the specification it will likely continue to evolve.

The future of the digital repository is being developed, and we won’t know exactly how it will be implemented, or what repairs and innovations will be required to make it shine the way the Amherst College community requires. One of the ways I’m assured that we will embody repair and innovation is because of the community – between our team of developers and librarians working to ensure a sound system here at Amherst College, and the larger Fedora community that we are a part of. We think of technology often as a lonely and isolated aspect of our modern world, but for those of working the digital library systems at Amherst College, it indeed embodies a dynamic community of care, and a set of tools we care deeply about, because they preserve our culture, our history, and help us to create the future we hope for. Barn-raisings were a common way to build a barn at one point in the history of the United States, and served as a way of leveraging all the skills of the community to help out a neighbor. I see the work we are involved in with Fedora as a kind of barn-raising, or a barn-renovating, and one that will help us out, but will help out countless other libraries and cultural heritage organizations preserve their treasures. The recent release of the Fedora API Specification is a testament to this effort to work together and make something even more people can use. To preserve things, it isn’t just the technology, it is the people doing the technology, that is going to give us a modicum of trust that things will survive in this digital age.

Este Pope is the Head of Digital Programs for the Frost Library at Amherst College. She can be contacted @ epope at amherst dot edu.